Table of Contents:

Comprehensive Guide to CNC Hole Machining: Methods, Instructions, Types, and FAQs

- November 20, 2024

- Tony

- Last updated on November 4, 2025 by Lucy

CNC hole machining is one of the important technologies in modern manufacturing. Whether it is the connection, assembly, or functional design of parts, various types of hole machining processes are indispensable.

1. What is CNC hole machining?

CNC hole machining is the use of CNC technology to machine holes in the workpiece or the process of finishing existing holes. High efficiency and high accuracy can be achieved through the precise control of CNC machine tools.

The importance of holes.

Hole making seems simple, but it’s where most machining jobs succeed or fail. Whether they are screw holes, pin holes or rivet holes for connecting parts, or mounting holes for fixing transmission parts, or even special-purpose holes such as oil holes, process holes or weight reduction holes, they are indispensable to the operation of the machine.

Whether it’s for bolts, bearings, or fluid passage, getting holes right is non-negotiable.

2. Common CNC Hole Making Methods That Work

Drilling: Your basic hole starter. Twist drills get you close, but never expect better than ±0.1mm tolerance from drilling alone.

Reaming: For when “close enough” isn’t good enough. Reamers give you that sweet H7 fit for pins and bearings.

Boring: When you need big holes or tight tolerances. We can hold ±0.005mm on diameter with the right boring head.

Honing: For surface finishes that seals actually seal against. Perfect for hydraulic cylinders.

Broaching: For those weird internal shapes that keep engineers up at night.

3. Common CNC hole machining instructions

In CNC machining, different hole machining tasks require the use of specialized instructions.

The following are some common CNC hole machining instructions:

- G81: Standard drilling cycle, suitable for general shallow hole machining.

- G82: Drilling cycle with pause, used to improve the bottom finish of the hole.

- G83: Deep hole drilling cycle, which effectively solves chip removal problems through segmented feeds.

- G84: Tapping cycle, specialized for machining threaded holes.

- G85: Reaming cycle, suitable for high precision and high finish hole processing needs.

- G86: Boring cycle for finishing deep or large holes.

- G89: Slow exit cycle, usually used for honing process.

📌Case Study: Aerospace Manifold Block

The Challenge: An aerospace customer needed 500 aluminum manifold blocks with 47 precision holes each. The part had intersecting fluid passages, threaded ports, and tight tolerances that would make most machinists nervous.

Our Solution: We developed a multi-stage hole making process with in-process verification.

Hole Making Details:

- Material: 7075-T6 Aluminum

- Hole Types and Requirements:

- 12x Main fluid passages: 8.0mm ±0.02mm, Ra 0.8μm

- 8x Cross-drilled intersections: 4.2mm ±0.05mm, positional tolerance 0.1mm

- 18x M6 threaded ports: 5.0mm drill + tap, 12mm deep

- 6x O-ring grooves: 22.5mm ±0.01mm, 2.5mm wide ±0.05mm

- 3x Sensor mounting holes: 6.5mm H7 fit, Ra 0.4μm

- Machining Strategy:

- Center drill all locations first for positioning

- G83 peck drilling for holes deeper than 15mm

- G85 boring cycle for critical diameter holes

- In-process probing after each operation

- Custom coolant-through tooling for deep holes

- Quality Results:

- First-pass yield: 99.6% (vs. customer’s 95% requirement)

- Hole position accuracy: All within 0.08mm of true position

- Surface finish: Consistent Ra 0.6-0.8μm on all critical holes

- Thread quality: 100% go/no-go gauge acceptance

- Leak testing: Zero failures in pressure testing to 250 PSI

- Production Efficiency:

- Cycle time: 18 minutes per part (35% faster than estimated)

- Tool life: 400 parts per drill set (vs. expected 250)

- Setup time: Reduced from 45 to 12 minutes through standardized processes

The key insight was using carbide drills with through-tool coolant for the deep intersecting holes. This prevented chip packing and eliminated the need for secondary operations.

- Standard Holes: Drilling + reaming/boring for bearing fits and precision locations

- Deep Holes: Peck drilling with specialized drills – chip control is everything

- Small Holes: Micro-drilling or laser drilling when smaller than 1mm

- Complex Shapes: Boring or broaching for internal grooves and special profiles

The following table is provided for reference:

Hole Type | Examples | Characteristics | Common Machining Methods |

Standard Holes | Bearing holes, pin holes, threaded holes | Moderate precision, regular shape | Drilling + Reaming/Boring |

Deep Holes | Gun barrels, hydraulic pipes | High depth, requires efficient chip removal and cooling | Deep hole drilling, boring |

Special-Shaped Holes | Internal splines, tapered holes | Complex shapes, high demands on tools and machines | Broaching, boring |

Small Holes | Nozzle holes, medical instrument holes | Small diameter, requires high precision | Micro-drilling, laser drilling |

Fine Holes | Microelectronic component holes | High depth-to-diameter ratio, smooth finish required | Laser processing, EDM |

Slot Holes | Hydraulic valve slots, gas channels | Long and narrow, often used in specialized structures | CNC milling, wire cutting |

5. Tool Selection: What Actually Makes a Difference

1. Drill Bits: More Variety Than You'd Think

In the process of CNC machining parts, selecting the appropriate drill bit is crucial. Different types of drill bits are suited for varying machining requirements and material properties. Below are common drill bit types and their application scenarios:

Twist Drill

Twist drills are the most common general-purpose drills, featuring a helical design for machining a wide range of materials, including metal, wood, and plastics. They are characterized by high chip removal efficiency and are suitable for routine drilling and medium precision machining in mass production.

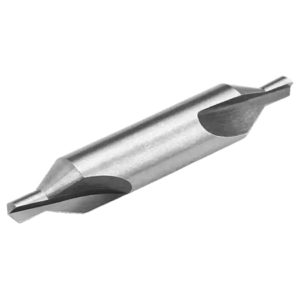

Center Drill

Center drills are used to locate holes for machining cylindrical workpieces, which can improve the accuracy of the holes. Its simple design, consisting of a sharp center edge and two cutting edges, is particularly suitable for initial machining of steel, cast iron and other high hardness materials.

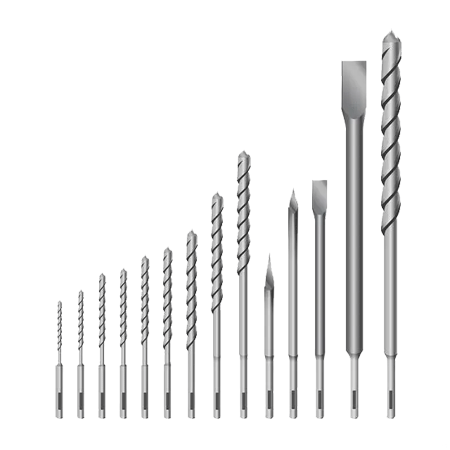

Deep Hole Drill

Deep hole drills have a longer structural design and are made for machining deep holes. Their good chip removal capability makes them suitable for large workpieces or scenarios where deep hole machining is required.

Step drills

Step drills can complete multi-stage drilling in a single pass, significantly reducing the number of drilling steps and increasing machining efficiency, and are commonly used for workpieces requiring multi-size holes.

Carbide Drill

These drills are made of cemented carbide with high hardness and wear resistance, suitable for hard materials and high-precision machining, with long service life, making them the first choice for precision machining.

Solid Drill

Solid drills have a simple structure, consisting of a center edge and two cutting edges, and are mainly used for the machining of small-hole parts. They are highly adaptable and can be used for machining a wide range of materials such as metals, plastics and wood.

Reamer Drill

Reamer drills combine the functions of reaming and drilling, suitable for processing thin-walled structural parts or workpieces requiring high-precision holes, with complex structure and various functions.

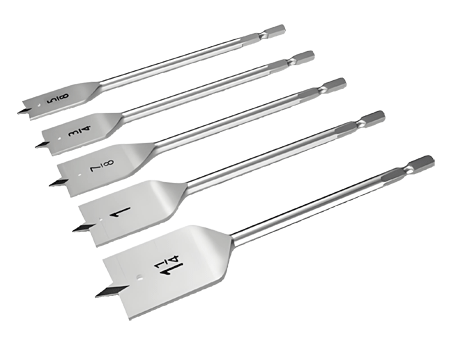

Flat Drills

Flat drills are mainly designed with a flat cutting edge, with a simple and low-cost structure. They are mainly used for drilling holes in soft materials such as wood and plastics, and are an economical choice for simple machining.

High Speed Steel Hollow Drills

HSS hollow core drills, also known as core drills, are suitable for magnetic drills and other equipment, and can be used for large hole processing or coring operations, with a variety of diameter specifications to meet a variety of processing needs.

Hammer Drill Bits

Hammer drills are designed for concrete, brick and other hard building materials, and are used in conjunction with electric hammer machines for high drilling efficiency, making them indispensable tools in construction projects.

2. Reamers: Hand vs Machine

Machine reamers: What we use in CNC operations. Straight flutes for general work, spiral flutes when you need a better finish or are cutting interrupted surfaces.

Hand reamers: For manual work or field repairs. Slight taper on the end makes them easier to start.

Shell reamers: For larger holes (over 25mm). The arbor is separate, so you can swap reamer heads without replacing the whole assembly.

Material matters: HSS works fine for most materials. Carbide lasts longer in abrasive stuff but costs 3× as much. Do the math on your production volume.

3. Boring Tools: Single Point Precision

Boring bars: Solid carbide for rigidity in small diameters, steel with carbide inserts for larger work. The longer the bar, the more it wants to chatter—sometimes you need multiple operations with different tool projections.

Boring heads: Adjustable to 0.001mm or better. We’ve got digital readouts on ours now—way better than cranking a micrometer dial and hoping you counted the rotations right.

4. Taps: The Right Tool Matters

Hand taps: Come in sets (taper, plug, bottoming). We rarely use these in CNC work anymore.

Spiral point taps: Push chips forward. Perfect for through-holes in steel. Not for blind holes unless you enjoy digging out packed chips.

Spiral flute taps: Pull chips back out. Your only real choice for blind holes. More expensive, but worth it.

Form taps: Don’t cut—they displace material. Stronger threads, no chips, but need softer materials (aluminum, brass, mild steel under 35 HRC).

6. Machining Parameters: The Numbers That Actually Matter

Here’s the thing about cutting parameters: the textbooks give you starting points, but your actual numbers depend on material, tooling, machine rigidity, and what finish you need.

Cutting Speed (Surface Speed)

This is how fast the cutting edge moves past the material. Too slow and you waste time; too fast and you burn up tools.

Real-world speeds I actually use:

- Aluminum (6061): 150-300 m/min for HSS, 300-600 m/min for carbide

- Mild steel: 30-50 m/min for HSS, 100-200 m/min for carbide

- Stainless (304/316): 20-40 m/min for HSS, 80-150 m/min for carbide

- Titanium: 15-30 m/min (go slow, stay sharp, use coolant)

Feed Rate

How fast the tool advances into the work. This affects chip formation, surface finish, and tool life.

What I actually run:

- Drilling: 0.1-0.3mm/rev (0.1 for small drills, 0.3 for large robust ones)

- Reaming: 0.3-0.5mm/rev (faster than drilling—reaming likes feed)

- Boring: 0.05-0.15mm/rev (slower for better finish)

- Tapping: Calculated automatically (pitch × RPM)

Feed too slow in a reaming operation and you just rub—creates work hardening and poor finish. Feed too fast when boring and you get chatter marks.

Depth of Cut

How much material you remove per pass.

Practical guidelines:

- Roughing: 2-5mm for drilling (depends on hole size)

- Finishing: 0.1-0.3mm for boring (light cuts = better finish)

- Reaming: 0.2-0.5mm stock removal total (not per pass—total)

I see a lot of engineers over-specify this. A 0.05mm finish cut in steel doesn’t give you a meaningfully better hole than 0.15mm—just costs more time.

Coolant: Not Optional

Flood coolant does three things: cools the tool, lubricates the cut, and evacuates chips. All three matter.

When I use through-tool coolant:

- Deep holes (anything over 5× diameter)

- Hard materials

- Small diameter drills that break easily

- When I need maximum tool life

Pressure matters too. 20 bar is adequate for most work. 60+ bar for deep hole drilling. The coolant stream physically pushes chips out of the hole.

7. Tolerance and Fit: What Different Specs Actually Mean

When someone specs a hole, the tolerance tells you what process you need.

Real-world tolerance guide:

- H14 to H12: Standard drilling (±0.2-0.5mm depending on size)

- H11: Careful drilling or rough reaming (±0.1mm)

- H9 to H7: Reaming or boring (±0.01-0.03mm)

- H6 and tighter: Precision boring or grinding (±0.005mm or better)

Here’s the thing: every step tighter costs money. An H11 hole might cost $2 to make. That same hole to H7? Maybe $8. To H6? Could be $25 with inspection time.

Common fits and what they mean:

- Clearance fit (H9/e8): Loose, for bolts with washers

- Slide fit (H7/g6): Close, but still moves freely

- Location fit (H7/h6): Tight enough to locate, loose enough to assemble by hand

- Press fit (H7/p6): Needs hydraulic press or heat

Don’t over-specify. If a clearance hole works, don’t call for H7.

Ultimately, the key to mastering tolerances and fits lies in minimizing friction—both within components and throughout the manufacturing process. For more details, please refer to the Comprehensive Guide to Tolerances and Fits.

8. FAQS

Three common culprits: tool sticking out too far, weak tool holder, or wrong feed rate. Keep tool extension under 5x diameter and use hydraulic holders.

Use peck drilling (G83 cycle), high-pressure coolant (1000+ PSI), and full retraction every 10mm for chip clearing.

Always center drill first. Use higher RPM (5000+ for steel) and gentle feed rates (0.02-0.05mm/rev).

Not accounting for thermal expansion. Machine and tools grow when warm – first parts often measure different than later ones.

Use sharp tools, proper speeds/feeds, and through-tool coolant. Sometimes faster feed rates actually give better finish.

Usually workpiece fixturing or machine wear. Check your clamps and verify machine geometry regularly.

Use flat bottom drilling or milling cutter machining, through the CNC programming to control the cutting path.

Use special groove cutter for machining, can also use CNC lathe combined with groove milling operation.

Check the tool wear, adjust the processing parameters or use reaming, boring process to complete the correction.

Use reaming or honing process for finishing, and check the accuracy of equipment and fixture stability.

Prioritize the use of high-precision center drill positioning, while ensuring the stability of machine tools and fixtures.

Bring it to us early. We’ll review your design, suggest improvements if there are any, and give you a realistic quote with actual lead times—not what you want to hear, but what’s actually achievable.